Dartmoor Gliding Society - Ed Borlase

Ed Borlase is a Bronze level Glider operator in Devon, and part of the Dartmoor Gliding Society. Here he tells us the crucial role the weather, weather forecasts and data play in being able to fly safely.

How did you get into gliding?

I’ve had a passion for aviation ever since I turned the page of my first Biggles book (the pilot adventure series by Captain W. E. Johns) around the age of six. From that point on I was hooked – it was all I wanted to do! Realistically though, flying itself seemed completely out of reach until I discovered and joined the Air Training Corps (ATC) at 13.

As it does for so many, the ATC gave me the gift of experiencing my first ever powered flight. I vividly remember the pilot looking at me just before we took off and saying, ‘let’s hope this is the start of something special for you’. I was so nervous that I didn’t look beyond the instrument panel at first, so completely missed the ‘big moment’ we became airborne, only realising we were up as we suddenly banked to the left and I found myself staring down a wing now pointing at a line of cars a few hundred feet below. I absolutely loved it!

There were gliding courses available through the cadets, but places were limited, so it ended up being something I couldn’t take advantage of at the time. However, I knew for certain that I’d return to gliding at some point in the future, and a few years ago I was given a voucher for a trial flight at Dartmoor Gliding Society (DGS) - I haven’t looked back since.

Gliding is a real adventure sport; it’s often referred to as ‘chess in the air’ which is a great way of putting it. You’re constantly searching for and trying to maximise the best lift, building up a mental picture of what the sky is doing around you while of course actively flying the aircraft, keeping a good lookout, navigating and staying aware of airspace among many other considerations. The workload can be extremely high, particularly if you’re low down, but the satisfaction and sense of achievement you get from staying up is immense, regardless of if you’ve just completed a long distance 5-hour cross-country task or merely ‘scratched around’ in broken lift for 12 minutes on a grey and tricky day.

Dartmoor Gliding Society has just celebrated its 40th Anniversary and is located on the western edge of Dartmoor National Park, near the village of Brentor in Devon. The picturesque 12th century St Michael de Rupe church on the tor itself forms an iconic backdrop to every flight, it’s a beautiful location.

What point in your training have you reached?

I’ve achieved my Bronze qualification which means I can fly solo under the licence of an instructor and am about to complete my cross-country endorsement, which will complete my full license.

Following Bronze, you have the option to progress through Silver, Gold and Diamond levels plus various Diplomas. The Diamond badge involves a distance flight of no less than 500km (the equivalent of Dartmoor to Bicester and back) which can take many hours. One of our club pilots, Richard Roberts, is a real trailblazer and has come the closest to achieving this from our site – read more about his record flight.

Gliding is extremely accessible and is one of the most affordable forms of aviation. You can learn to fly from as young as 14, and most clubs in the UK are run by volunteers, bringing the costs down significantly (a winch launch costs £9 and 42p per minute if you’re in a club glider at DGS).

How does the weather impact gliding?

In every way!

Alongside other factors including wind strength and gusts, rain and visibility that affect our ability to safely fly, there are three basic ways gliders stay in the air: thermal lift, ridge lift and wave lift. Thermal lift (also known as convection) is where the sun heats the ground, which in turn heats the air above, and this warm air then rises. As it rises, it cools and expands, forming clouds when the air has cooled to the dew point and the moisture (if present) condenses.

These ‘fair weather clouds’, with flat bottoms and fluffy white tops form a clear marker in the sky for glider pilots to head towards. People often think of gliders circling around in the sky and that’s because we’re doing so to stay in the core of the thermal, the centre of the rising air. A lot of gliding in the UK is based around thermal lift and that's where a lot of the skill and the challenge comes in.

Ridge lift is where a hillside or ridge gets in the way of the air, forcing it upwards. Gliding becomes sort of like surfing; you can beat up and down a ridge which can stretch for miles. You can fly pretty low compared to other types of lifts so it's a very different type of flying and can be quite unnerving, but if you understand how to find that lift and use it you can be up for hours and travel long distances.

The third kind is wave lift, and this is essentially when the air ‘bounces’ over large ground features such as mountains or hills and this ‘bounce’ creates standing waves, or long bars, of smooth lift higher up in the atmosphere. It’s very similar to river water passing over stones where standing waves form further downstream. You can often spot this from the ground as lenticular clouds (Altocumulus lenticularis = ‘like a lens’) often form. When you’re in the positive ‘up’ part of this lift, it is incredible smooth and stable and you can fly in a straight line, climbing all the time and reaching great heights. The record over Dartmoor in these conditions is a whopping 16,500ft!

What part does weather information play?

Weather information is vital for planning and decision making, both in regard to the potential we have to stay in the air, and whether or not conditions are safe to fly in at all in the first instance.

We use a range of weather information including Met Office synoptic weather charts through the Aviation Briefing Service. The synoptic charts are great for understanding the broader context of how the major pressure systems are moving, and we tend to look at these from up to a week out to start to gauge what we can expect in terms of wind direction, strength and the stability of the atmosphere.

As we move closer to a flying day, we’ll then look increasingly at more detailed information.

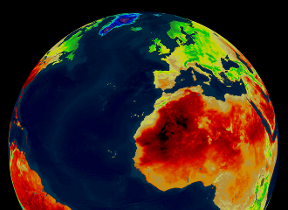

Sources such as windy.com which uses Met Office data are fantastic for visualising wind direction and strength, comparing different forecast models, showing cloud cover, cloud base, live rainfall radar, and even route planning.

Two key briefing charts provide by the Met Office Aviation Service that we reference on the day are 1. ‘F214’, a spot wind chart showing forecast wind speed, direction and temperature at various grid points and altitudes across the UK, and 2. ‘F215’, a chart that shows areas of weather across the UK from the surface up to 10,000ft. This chart uses both graphics and alphanumeric codes to present detailed information all on one sheet, and we use it to build up an understanding of factors we can expect in our region such as visibility, turbulence, cloud type and cover, potential for and type of precipitation, cloud base and tops, freezing altitude etc, and base operational flying decisions with these in mind. These charts are issued 4 times a day every 6 hours.

Is accuracy in weather forecasting important?

Accuracy is essential for good planning in order to set expectations for the day, and for fundamentally ensuring that we will be within the safe limits to fly. For example, too much of a cross-wind will take particular gliders outside of their safe operating envelope.

Cross-referencing different forecasts helps us to build up a well-rounded picture of what we can expect, and we find your local forecasts for the surrounding area such as Tavistock match what we see on the airfield very closely.

Using forecasts to understand how high thermals might be operating and what cloud base we can expect to see is essential and part of our training. We’re always trying to build an understanding of how the day might pan out, and it becomes particularly important when you start thinking about cross country flights where you might be moving through weather systems, or the weather might change over the course of a longer flight. It's great to be able to have free access to all these tools and information.

I always find it amazing when you actually see the forecast playing out in front of you as predicted; whether it’s being stuck on the ground in an intense downpour of gusty rain as a cold front pushes its way through, or when you really feel the power and strength of a thermal as it’s lifting you upwards at a rate of 800ft a minute – it’s all pretty incredible!

Putting it to the test

Ed put our Presenter Aidan Mcgivern to the test by inviting him to come and do a meteorological briefing for the team and then test out the accuracy of his briefing by swapping our weather studio for a 2-person glider 1500ft above the ground. You can see how he gets on in this video.