La Niña slows atmospheric CO₂ rise: but not for long

Author: Grahame Madge

00:01 (UTC) on Fri 27 Jan 2023

Carbon-dioxide will continue to build up in the atmosphere in 2023 due to ongoing emissions.

However, the Met Office predicts a slower build-up than usual this year because of a temporary increase in natural carbon sinks – processes which absorb more carbon-dioxide.

This effect will not be permanent, and will need to be replaced by rapid cuts in emissions if global warming is to be limited to 1.5°C.

To achieve that goal, the build-up of CO₂ needs to become slower and ultimately stop in about a decade’s time. By chance, temporary planetary cooling – as a result of La Niña in the tropical Pacific – is currently slowing the CO₂ build-up by encouraging tropical forests and other vegetation to soak up more carbon-dioxide than usual for the third year running.

So, while CO₂ levels in the atmosphere continue to increase due to emissions from fossil fuel burning and deforestation, this increase is smaller than it would have been without the extra carbon uptake by remaining forests.

To follow the 1.5°C scenario, the increase needs to keep becoming smaller year-on-year. This would only be possible through rapid and deep cuts in global emissions.

Professor Richard Betts MBE - who leads the team behind the CO₂ forecast – said: “Although our forecast is for a slower build-up again this year, this is not because humanity is emitting less carbon. Instead, we are getting a free ‘helping hand’ from nature – but only for now. Once La Niña weather patterns have ceased, more of our emissions will remain in the atmosphere. We cannot rely on nature to do our job for us.”

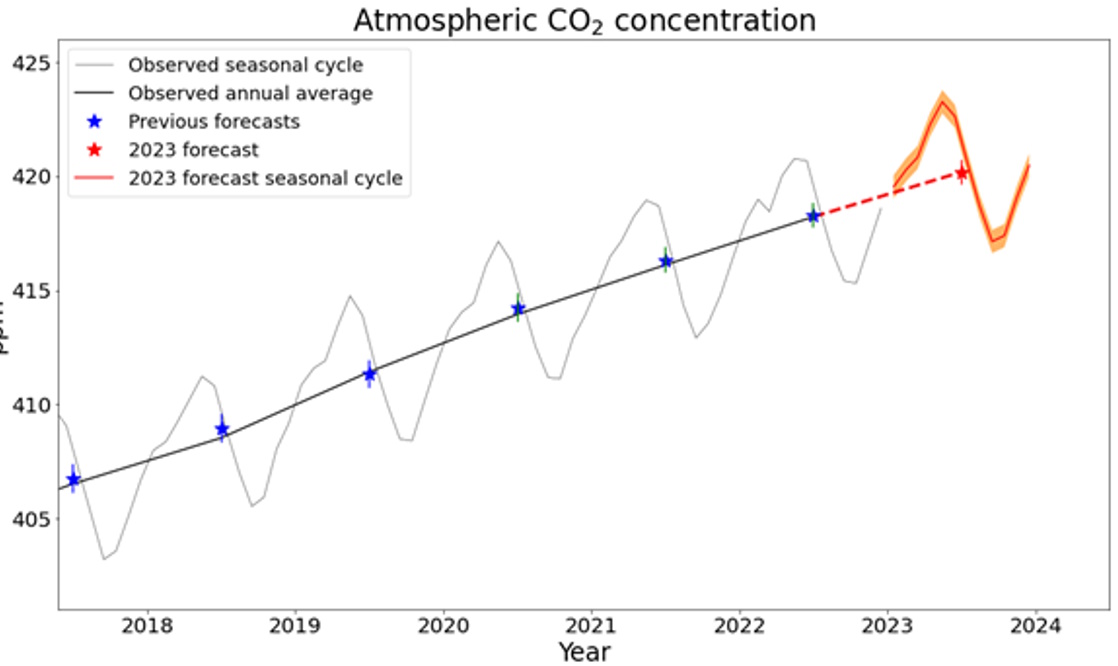

The Met Office forecast calculates the annual average CO₂ concentration at Mauna Loa, in Hawaii, to be 1.97 ± 0.52 parts per million (ppm) higher in 2023 than in 2022. Without the masking effect of La Niña, the rise would have been 2.3ppm parts per million.

Prof Betts added: “At first sight, this year’s CO₂ rise might appear to be in line with a scenario for limiting global warming to 1.5°C, but actually this is a false impression. It is happening only temporarily, and not for the right reasons. Once the current La Niña abates, its ability to draw down carbon-dioxide will be lost, allowing CO₂ in the atmosphere to grow faster.

“The 1.5°C scenario requires a determined year-by-year decline in the rate of atmospheric CO₂ rise, starting immediately and reaching zero in the 2030s.

“Rapid, large-scale cuts in global emissions are needed to achieve this. These are not reflected in current global pledges and policies, as reported in the IPCC WG3 report.”

The forecast predicts that the average concentration of carbon-dioxide this year will reach above 420 ± 0.5 ppm (parts per million) at the observing station in Mauna Loa in 2023. This will be the first time that these levels have been reached in the ‘Keeling Curve’ record, which dates back to 1958. When the record began, CO₂ levels were around 316ppm and increasing at less than one part per million per year.