What are the different types of wind?

This rising and sinking of air in the atmosphere takes place both on a global scale and a local scale.

Small-scale winds

One of the simplest examples of a local wind is the sea breeze. On sunny days during the summer the sun's rays heat the ground up quickly. By contrast, the sea surface has a greater capacity to absorb the sun's rays and is more difficult to warm up - this leads to a temperature contrast between the warm land and the cooler sea.

As the land heats up, it warms the air above it. The warmer air becomes less dense than surrounding cooler air and begins to rise, like bubbles in a pan of boiling water. The rising air leads to lower pressure over the land. The air over the sea remains cooler and denser, so pressure is higher than inland.

So we now have a pressure difference set up, and air moves inland from the sea to try and equalise this difference - this is our sea breeze. It explains why beaches are often much cooler than inland areas on a hot, sunny day.

Large-scale winds

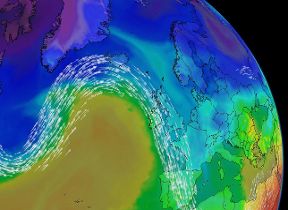

A similar process takes place on a global scale. The sun's rays reach the earth's surface in polar regions at a much more slanted angle than at equatorial regions. This sets up a temperature difference between the hot equator and cold poles. So the heated air rises at the equator (leading to low pressure) whilst the cold air sinks above the poles (leading to high pressure). This pressure difference sets up a global wind circulation as the cold polar air tries to move southwards to replace the rising tropical air. However, this is complicated by the earth's rotation (known as the Coriolis effect).

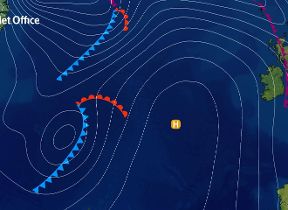

Air that has risen at the equator moves polewards at higher levels in the atmosphere then cools and sinks at around 30 degrees latitude north (and south). This leads to high pressure in the subtropics - the nearest of these features that commonly affects UK weather is known as the Azores high. This sinking air spreads out at the earth's surface - some of it returns southwards towards the low pressure at the equator (known as trade winds), completing a circulation known as 'global circulation patterns'.

Another portion of this air moves polewards and meets the cold air spreading southwards from the Arctic (or the Antarctic). The meeting of this subtropical air and polar air takes place on a latitude close to that of the UK and is the source of most of our weather systems. As the warm air is less dense than the polar air it tends to rise over it - this rising motion generates low-pressure systems which bring wind and rain to our shores. This part of the global circulation is known as the mid-latitude cell.

Another important factor is that the Coriolis effect from the earth's rotation means that air does not flow directly from high to low pressure - instead it is deflected to the right (in the northern hemisphere - the opposite is true in the southern hemisphere). This gives us our prevailing west to southwesterly winds across the UK.