Lessons and legacy of the Great Storm of 1987

The Great Storm of 1987 affected many parts of the UK on the night of 15-16 October. With wind gusts of up to 100mph, 18 people were killed, millions of trees blown down and transport seriously disrupted.

The developing storm

Forecasters had been predicting severe weather severe days ahead of the storm. But models suggested severe weather would pass to the south of England, only skimming the south coast.

Although autumnal storms typically arrive from the Atlantic to the west of the UK, this storm developed over the Bay of Biscay to the south.

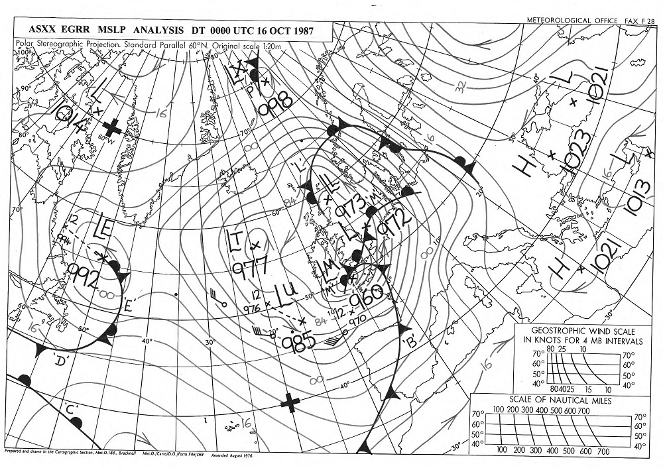

Particularly warm tropical air and very cold polar air collided, forcing warm air to rise creating an area of low pressure. A big difference in temperature between the warm and cold air helped to cause a rapid ascent and a particularly low pressure system. To the west of the low, pressure rose rapidly leaving a big differential in pressure, which can be seen in the tightly drawn isobars of the chart below.

A synoptic chart for the Great Storm of 1987

Was the storm a hurricane?

Many people remember the words of BBC weather forecaster Michael Fish on the lunchtime news before the storm struck:

"...earlier on today apparently, a woman rang the BBC and said she’d heard there was a hurricane on the way. Well, if you are watching, don’t worry, there isn’t….."

Fish was talking about a separate storm over the western part of the North Atlantic Ocean on that day. He said it wouldn’t reach the UK, and it didn’t. But the rapidly deepening low from the Bay of Biscay did.

This storm wasn’t officially a hurricane, because they need specific conditions found in the tropics to form. But hurricane-force winds did occur in some locations in the UK during the Great Storm.

In the video below, Michael Fish and Alex Deakin reflect on their memories of the Great Storm of 1987 and explain how forecasting has improved since then.

Why the storm was 'great'

Several factors came together to make the 'great' storm so ferocious, but it was the track of the storm that was probably most significant.

Arriving over the south coast of the UK, it tracked north and east before reaching the Humber estuary at about 5.30am on 16 October. This path included a large built up and densely populated area of the UK, exacerbating its impacts.

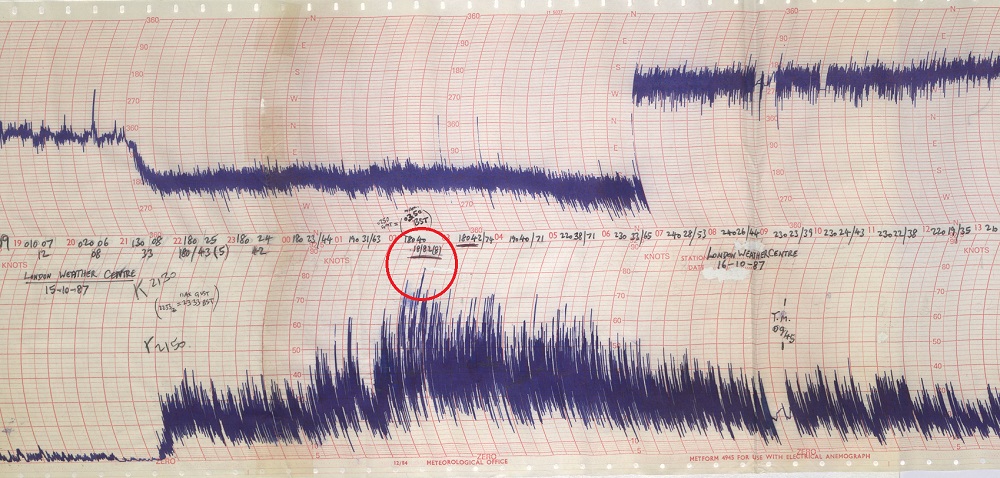

In southeast England, where the greatest damage occurred, gusts of 80mph were recorded for three to four consecutive hours. The highest gust recorded over the UK was 115mph at Shoreham on the Sussex coast at 3.10am. Gusts of more than 100mph were recorded at several other coastal locations. Inland gusts exceeded 90mph, with 94mph recorded at London Weather Centre at 2.50am.

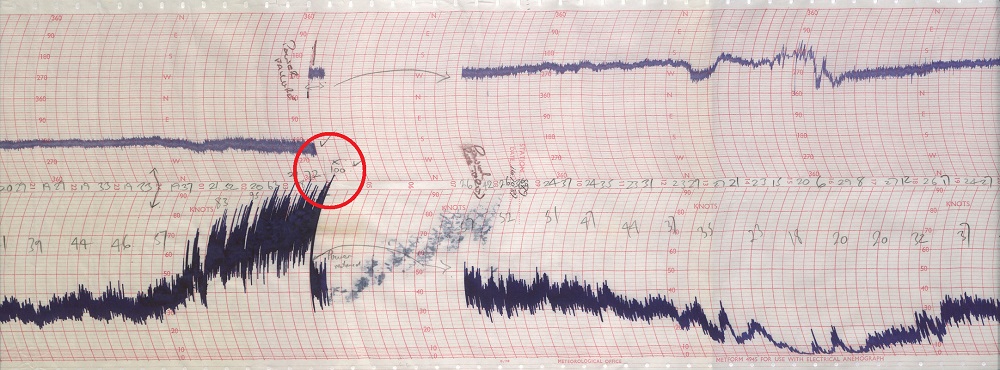

An image of an anemogram from Shoreham, West Sussex where a 115mph (100 knot) gust was recorded. This gust was followed by a power cut shown by the gap in the trace.

An image of an anemogram from London Weather Centre showing the 94mph gust recorded at 2.50am.

Learning from the storm

After the storm, it became clear the Met Office and other European forecasters did not have the capability to forecast such an event. The storm became a catalyst for a programme of investment and improvement in the science, technology and communication of forecasting, which has since transformed the way the UK understands and responds to severe weather.

The strength of the 1987 storm was boosted by a phenomenon known as the ‘Sting Jet’. This occurs when cold dry air from high in the atmosphere descends into weather systems, creating an area of particularly strong winds at ground level. At the time of the storm, no one knew these existed, but now they are well understood within meteorology and included in forecast models.

Improving our observations

Forecasting has also improved, due to an increase in the amount of data from satellites. In 1987, very few observations were received from satellites. Since then, the majority of Met Office observations have come from satellites and contribute significantly to our global numerical weather prediction model.

Additonally in 1987, only a small number of observations were taken from the Bay of Biscay where the storm formed. Due to the storm, deep ocean weather buoys were located around the British Isles to provide hourly weather information and improve our monitoring of developing weather conditions.

Advancing our technological capability

Supercomputing capability has also hugely advanced since 1987. The Met Office supercomputer in 1987 could perform four million calculations per second, but had less computing power than a modern-day smartphone. The current supercomputing system is able to perform 14,000 trillion calculations per second, helping to unlock new science and provide more detailed forecasts and warnings.

In 1987, computing capacity limited the resolution of the global model used for weather prediction to grid boxes of 150 km. In more recent years, the model has worked at 10 km on a global scale, giving vastly improved resolution. Over the UK, these grid boxes have been reduced to just 1.5 km, leading to improved forecast accuracy.

Additionally, unlike 1987, we now run multiple forecasts (called ensembles). They help us to understand the probabilities involved in a forecast and give a better estimate of the risk of high impact weather events.

The video below shows how the Great Storm may have been forecast if it had happened 30 years later.

The National Severe Weather Warning Service

Following the Great Storm of 1987, the Met Office set up the National Severe Weather Warning Service (NSWWS) to provide a coordinated way of delivering warnings to government, industry, emergency responders and the public. They are designed to help people prepare for and take action to avoid the impacts of severe weather such as heavy prolonged rainfall, storms and heatwaves.

Initially those warnings were faxed and emailed to emergency responders and other media organisations for broadcasting on TV and radio. Now most people in the UK get weather forecasts and warnings through mobile apps, social media and the web. They can also sign-up for Met Office alerts direct to their phone or email inbox.

Name Our Storms

In 2015, working in collaboration with the Irish meteorological service, Met Éireann, the Met Office launched a pilot project to name storms when it has the potential to cause a significant level of impact. By naming storms we help to provide a consistent message and aid the communication of approaching severe weather through media partners and other government agencies. In this way people are better placed to keep themselves, their property and businesses safe.