In the tense days leading up to VE Day, the skies above Britain carried more than just clouds, they held wartime secrets.

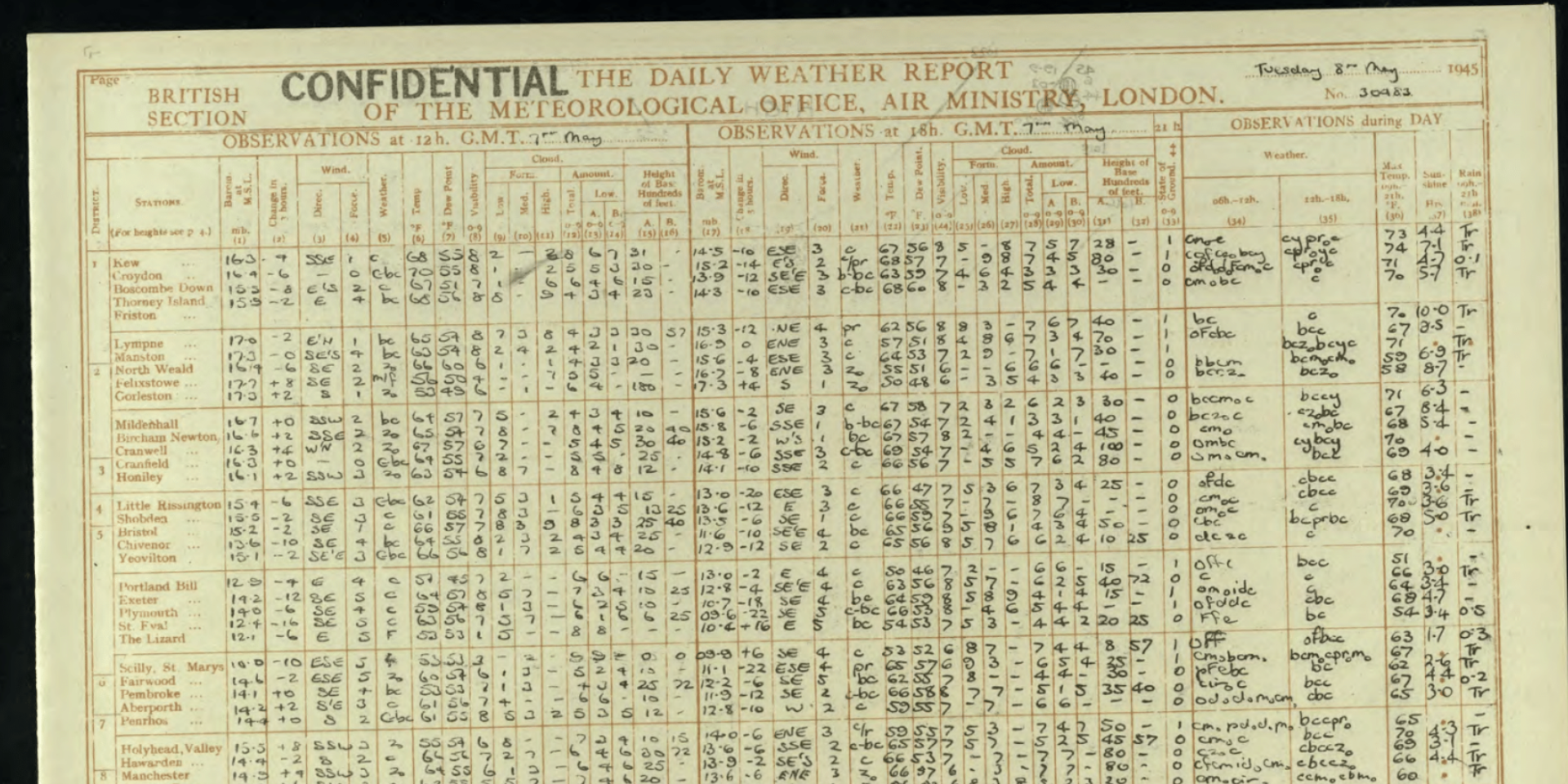

During World War Two, weather forecasts became classified information, vital to military operations and unavailable to the public.

Forecasts Go Silent

When war broke out in 1939, the BBC’s daily weather bulletins, which had been broadcast since 1923, were halted. The Met Office, which had been providing these forecasts, shifted its focus to supporting the war effort. Weather played a critical role in military planning, from the timing of D-Day to the movement of troops and supplies. As such, forecasts became top secret.

Dr Catherine Ross, library and archive manager at the Met Office, said: “Forecasting stopped at the announcement of the outbreak of war because your weather observations are really useful to your enemy.

“If you were to put out a radio broadcast that said it was going to be a lovely day and clear skies overnight, that information was very useful to your enemies in planning a bombing raid on your cities."

Forecasting for the Front and the Fields

While the public was kept in the dark, key sectors still received tailored forecasts. The Ministry of Fuel and Power and the Ministry of Transport received updates via secure telephone lines, particularly in winter months for snow and ice. But it was the agricultural sector that had the most consistent access, with forecasts helping farmers make critical decisions during harvest.

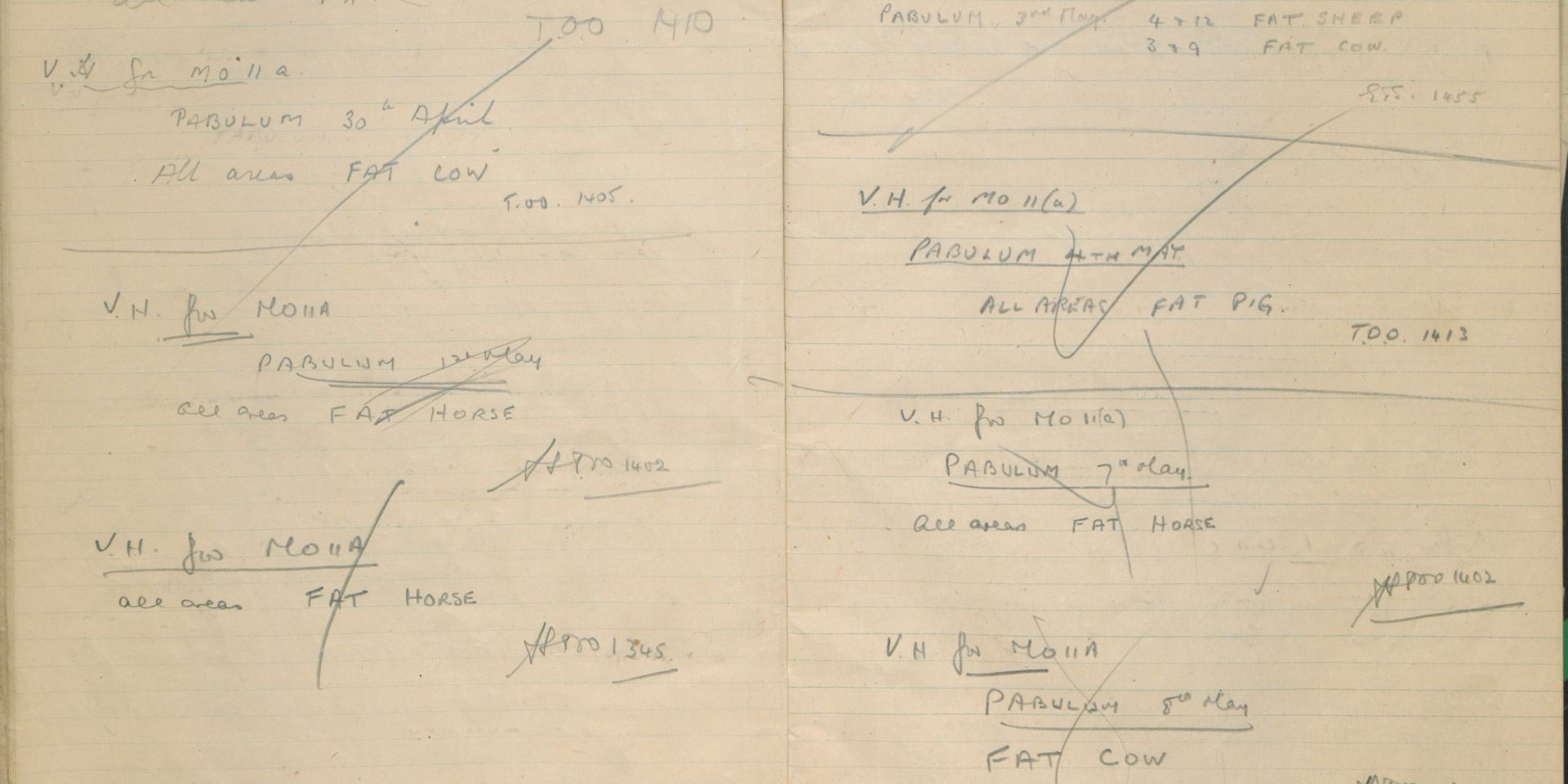

Farmers, in particular, needed to know when to protect crops or harvest in time. To meet this need, the Met Office developed a system of coded agricultural forecasts, distributed through the civil defence network. These forecasts used animal names, like “dog,” “sheep,” and “cow”, to describe conditions, and terms like “buy” for good weather, “sell” for bad, and “fat” for uncertainty.

Dr Ross continued: “We were making forecasts for a couple of government departments that needed information, so the Ministry of Fuel and Power and the Ministry of Transport both needed forecasts in snowy or very icy conditions. So, they were getting telephone forecasts to one or two nominated individuals, this information wasn’t going to everybody.

“Those forecasts were all coded. They were two-word forecasts, so you’d get one that would indicate what are the conditions and one that would say how long they were going to last for.

“For example, if you got ‘Ripe Lemons’ it would be “the temperature is going to be below freezing, day and night, and it’s going to be a prolonged cold spell.”

Codes for the Ministry of Fuel and Power used fruits, however, metals such as gold, steel and copper were used for the Ministry of War Transport, and flowers were used for the Ministry of Home Security.

Where did the forecasts come from?

Where did the forecasts come from?

At the start of the war, just 43 stations in the UK reported to the Central Forecasting Office at Dunstable. However, as the war progressed and new airfields and sites opened this number surged and, by 1945, totalled 552.

Gathering data from outside the British Isles was far more challenging. Observations were received from neutral and allied nations including Spain, Portugal, the Azores, Iceland, Canada, the US, and the Republic of Ireland. However, as Axis powers took control of much of Europe, official weather reports from those regions ceased.

Despite this, British forecasters still managed to access weather data from Axis-controlled areas. This was largely thanks to the breaking of German Enigma codes by cryptographers at Bletchley Park. Weather-related transmissions were decoded and passed to a special unit at Dunstable, helping to fill critical gaps in forecasting.

To address the loss of oceanic data due to radio silence on Allied ships, the Admiralty eventually deployed armed weather ships. Tragically, both vessels were sunk by U-Boats, resulting in the loss of 83 lives, including two meteorologists.

With military operations and air travel spanning much of the globe during World War Two, Met Office staff were deployed all over the world. Their role was to carry out weather observations, deliver forecasts, and provide critical advice to commanders and military personnel. They were supported by members of the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (Meteorological Branch), who had enlisted specifically to serve as wartime meteorologists.

In many locations, Met Office personnel worked closely with allied meteorological services, fostering collaboration and knowledge exchange. They also played a key role in training locally recruited staff in meteorological techniques. This training not only supported wartime operations but also laid the groundwork for the development of national weather services in several countries after the war.

Dr Ross explained: “Met Office forecasters were spread across all of the operational fronts. They were eventually brought back, but it would have taken months to actually get them all home.

“One of the things we do know is that Met Office forecasters who went out to these countries were training up local civilians, which led to the foundation of quite a lot of the local Met services, particularly in India and the far east. A lot of these services were founded after the war as a result of the training and set-ups that were developed during the war.”

VE Day: The Forecast Returns

It wasn’t until the end of the midnight BBC news bulletin on VE Day that the British public heard a weather forecast again for the first time in six years. This moment marked not just the end of war in Europe, but the return of a familiar voice in daily life—the weather forecast.

The Met Office’s archived forecast notebooks reflect this transition. From 9 May 1945, the coded language was dropped, and forecasts resumed in plain English. The final coded forecast for VE Day itself saw the outlook described as “fat cow”, likely meaning 'uncertain weather with rain early, clearing later.'

Keep up to date with weather warnings, and you can find the latest forecast on our website, on YouTube, by following us on X and Facebook, as well as on our mobile app which is available for iPhone from the App store and for Android from the Google Play store