How accurate are our public forecasts?

Accuracy is as important to us as it is to you. We innovate and refine our processes continually to make sure that the weather forecasts you access are as useful as they can be.

Thanks to this commitment to accuracy, our four-day forecast is now as accurate as our one-day forecast was 30 years ago.

Global recognition as a world-leading National Met Service

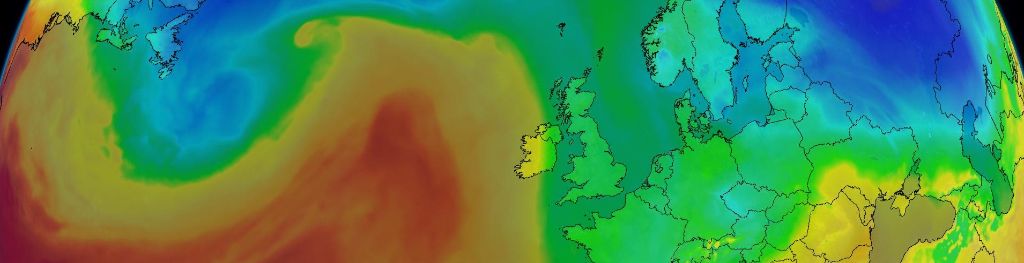

Striving for forecast accuracy is in our DNA. Our global Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) model, the foundation of our accurate weather provision, is verified using standards defined by the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). When compared against other global NWP producing centres, for both deterministic and ensemble forecasts, we are consistently recognised as in the top two forecast providers and as a world leading National Met Service.

Trusted for this expertise

The high level of trust in our forecast accuracy is underlined by the fact that our NWP model is used under licence by seven other forecast centres and over 50 research centres around the world.

The weather forecasts we produce are designed to help everyone stay safe and thrive. From the general public to businesses, critical infrastructure and governments. world-leading accuracy is essential in achieving this. And in ensuring we are a trusted weather provider.

Here are some of the many reasons you can trust us:

- Our role as one of just two World Area Forecasting Centres advising airlines operating right across the globe, means we help people get away on business and pleasure safely and efficiently when they want.

- Our accurate weather information helps protect your loved ones in UK forces on exercises and missions around the world. Throughout our history, we have been able to make a difference.

- Our space weather forecasts help keep the world’s technology safe from solar flares – keeping everyone connected.

- We have been helping to protect lives at sea for over 150 years by providing uninterrupted marine forecasts since 1867.

- We are the first National Meteorological Service to move to fully ensemble-based global and regional forecasting. Find out why this is a landmark development in ensuring future improvements in forecast accuracy.

- Our weather models harness the processing power and computational capacity of our supercomputer, helping us provide even more detailed data and forecasts and earlier warnings of severe weather.

Why are weather forecasts not always accurate?

Over the past 30 years, forecasting accuracy has been improving in leaps and bounds. To generate forecasts, meteorologists run computerised numerical weather models which analyse billions of observations to work out how the current conditions will develop into the future. Some weather models can be more or less accurate, some are better at forecasting certain weather types, others at forecasting at different lead times.

However, weather is a ‘chaotic’ system. This means small differences in conditions now, such as a shift in temperature, wind or humidity, can have a significant impact on the weather conditions we might see over the coming days. Even seemingly small discrepancies in the current conditions can lead to inaccuracies that grow as the forecast runs further into the future, and however good our observations, we can never know every detail of current conditions. Therefore, relying on ensemble modelling, where we run many simulations from very slightly different starting conditions, is much better than just one run of one weather simulation model.

Experienced meteorologists look at the range of simulations and determine the most likely outcome, as well as assessing the risks associated with other possible outcomes.

Many weather apps and website forecasts, including ours, are calculated using automated data taken directly from a combination of weather prediction models without any input from meteorologists.

This automated approach works very well in most situations and allows us to issue localised forecasts for a huge number of specific locations, but some automated location-based forecasts can struggle under some circumstances, particularly under extreme circumstances such as we saw in July 2022 when temperatures topped 40C at a number of locations.

Technological improvements along with our focus on ensemble forecasting and our world-leading experts means we will be able to keep improving our forecast accuracy.

When accuracy really matters

Here are some real-world examples of what others say about our forecast accuracy and what it means to them. A collection of people from backgrounds ranging from critical services to hobbyists have shared stories about how our forecasts help them at work and play.

Ed Borlase is a Bronze level Glider operator in Devon, and part of Dartmoor Gliding Society. He tells us the crucial role the weather, weather forecasts and data play in being able to fly safely.

Photographer James Hines explains how using our forecasts helps him locate the best time and place to capture the perfect atmospheric photograph.

The team at eat:Festivals - a not-for-profit social enterprise - explains how the weather can impact the food and drink festivals they run.

Photographer Nicola Turner explains how people use our forecasts to find the optimum place and time to take breath-taking photos of landscapes across the UK.

David Taylor, an emergency response officer within the British Red Cross response team, tells us why our forecasts and warnings are crucial to planning and preparedness.