Space weather may feel distant, unfolding far above Earth in regions we never see, but its impacts can be surprisingly close to home.

From power grids and satellite navigation to aviation and communications, space weather can influence many of the systems that underpin modern life. As our reliance on technology grows, so too does the importance of understanding, monitoring and forecasting activity that originates from the Sun.

The Met Office Space Weather Operations Centre (MOSWOC) plays a central role in this effort, operating around the clock to provide forecasts, warnings and guidance that helps protect national infrastructure. This article explores how the Met Office forecasts space weather, the science behind it and why this work is so critical.

The role of the Met Office Space Weather Operations Centre

MOSWOC is one of a small number of space weather prediction centres globally that operates 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Established in response to increasing national concern about the risks posed by severe solar events, MOSWOC supports government agencies, emergency responders, critical national infrastructure operators and the public.

Space weather was formally added to the UK Government’s National Risk Register of Civil Emergencies in 2011, recognising that a severe solar storm could have economic and societal impacts. The Met Office’s role is therefore twofold: to provide accurate and timely information about current and forecast conditions, and to help build resilience across industries that depend on reliable technology.

What space weather is and why it poses a threat

Space weather refers to variations in the Sun, the solar wind and the Earth’s magnetic environment that influence conditions both in space and on the ground. These variations include the emission of charged particles, radiation, magnetic fields and solar material.

While the aurora is the most familiar and visually striking effect of space weather, other impacts are far less benign. Space weather can:

-

disrupt radio communication systems,

-

distort or degrade global navigation satellite systems (GNSS/GPS),

-

interfere with satellite operations,

-

damage spacecraft hardware,

-

affect power grids,

-

increase radiation exposure for astronauts and high-altitude aviation.

As society increasingly depends on satellite-based systems, digital communications and interconnected infrastructure, vulnerability to solar activity has grown. Systems today must be designed to withstand a wide range of space weather conditions, making reliable forecasting essential.

Recent space weather events

A G4 geomagnetic storm occurred overnight on Monday, 19 January, generating vivid auroras widely across the UK wherever skies were clear. Visibility reports extended unusually far south, reaching as far as northern Italy. The magnitude of this storm was comparable to the significant event recorded in November 2025. No additional coronal mass ejections are anticipated in the current forecast.

READ MORE: Northern lights dazzle sky-watchers across the UK

Met Office Space Weather Manager Krista Hammond said: "We observed a G4 geomagnetic storm overnight on Monday into Tuesday, which was a similar level to the one seen in November last year. This event brought aurora visibility to much of the UK and some reports of viewings as far south as northern Italy. We would expect geomagnetic storms of this magnitude a couple of times a year at this point in the solar cycle. “

What drives space weather?

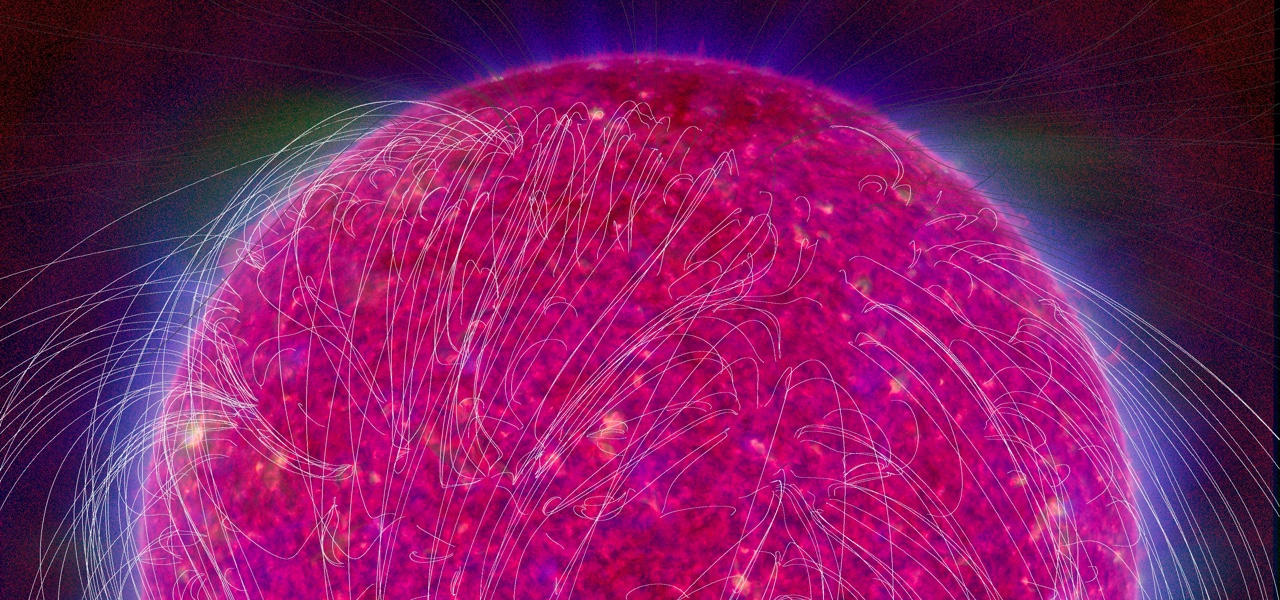

Space weather originates with the Sun. The Sun is dynamic and constantly active, producing magnetic fields, energetic particles and radiation that travel outward into the solar system. These emissions interact with Earth’s magnetic field and upper atmosphere, shaping conditions in near Earth space.

Three types of solar activity are of particular importance:

Coronal mass ejections

A coronal mass ejection (CME) is a large burst of solar plasma and magnetic field released from the Sun into space. If a CME is directed toward Earth, it can significantly disturb the planet’s magnetic field and ionosphere, potentially causing geomagnetic storms.

CMEs typically take one to several days to reach Earth, allowing some lead time for forecasting.

Solar flares

Solar flares are sudden releases of electromagnetic energy that occur across the spectrum. Unlike CMEs, the radiation from a solar flare reaches Earth in around eight and a half minutes. This rapid arrival means that flare induced effects, such as radio blackouts, can occur with little warning.

Flares are often associated with CMEs, making them an important diagnostic feature when assessing ongoing solar activity.

Highspeed solar wind streams

Even in quieter periods, streams of charged particles carried by the solar wind interact with Earth’s magnetic field. Disturbances increase during periods of elevated solar activity.

Extreme events, though infrequent, can occur at any time during the Sun’s 11year activity cycle.

How the Met Office forecasts space weather

Forecasting space weather involves combining scientific observations, modelling techniques and expert analysis. MOSWOC uses data from solar monitoring satellites, ground-based observatories and international partners to build a detailed picture of solar and geophysical conditions.

Key components include:

Monitoring the Sun

Satellites and ground observatories continuously track the Sun’s surface, magnetic fields and emissions. This includes monitoring:

-

sunspots and active regions,

-

solar flares,

-

CME eruptions,

-

solar wind speed and density,

-

radiation levels.

Forecasters assess whether a flare or CME is Earth directed and how it may evolve as it travels through space.

Modelling CME arrival times

Because CMEs take time to reach Earth, forecasting their arrival is a major focus. MOSWOC uses models that simulate CME trajectories and interactions with the solar wind. These tools allow forecasters to estimate the timing and severity of geomagnetic storms.

READ MORE: Space weather: How different types affect us

How space weather affects our technology

The impacts of space weather vary depending on the type and intensity of the event:

Radio blackouts

Solar flares can temporarily disrupt high frequency (HF) radio communications on the sunlit side of Earth by altering the ionosphere so that it absorbs, rather than reflects, radio signals. This can affect aviation, maritime operations and emergency communications.

Even during quieter conditions, turbulence in the ionosphere can distort GNSS/GPS signals, a problem known as scintillation.

Geomagnetic storms

CMEs can cause large disturbances in Earth’s magnetic field, leading to geomagnetic storms. These storms can result in:

-

power grid fluctuations or transformer damage,

-

spacecraft orientation problems,

-

disruptions to satellite-based navigation and timing systems,

-

interference with HF radio communications.

Solar radiation storms

High energy particles generated during large flares can rapidly reach Earth’s polar regions, increasing radiation levels at aviation altitudes and potentially damaging spacecraft electronics. While astronauts can avoid spacewalks during such events, satellites have no such protection.

Why forecasting space weather is increasingly important

Although severe space weather events are rare, their impacts can be substantial. With modern infrastructure increasingly interconnected and dependent on accurate navigation, timing and communication signals, even modest disturbances can have cascading consequences.

Industries most at risk include:

-

energy providers,

-

satellite operators,

-

telecommunications providers,

-

aviation and marine transport,

-

rail and road transport.

The Met Office works closely with these sectors to understand how space weather affects their operations and to develop tailored forecasts that help them plan, mitigate risk and maintain continuity.

Building resilience through forecasting

MOSWOC’s forecasts and warnings support national readiness by allowing organisations to take precautionary steps. These might include protecting sensitive equipment, rescheduling satellite manoeuvres, adjusting aviation routes or increasing monitoring of power systems.

Space weather forecasting is therefore a critical component of national resilience planning, ensuring that the UK remains prepared for both routine solar variability and the rare but potentially severe events that could have far reaching consequences.

You can find the latest forecast on our website, on YouTube, by following us on X and Facebook, as well as on our mobile app which is available for iPhone from the App store and for Android from the Google Play store.